Punk’s not dread. Back in the ’90s, Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon had “Girls invented punk rock, not England” emblazoned on a t-shirt. Photos of her sporting the slogan circulate every so often—I’ve been seeing them again lately on social media. I’m not sure what it means, I’m not sure if I agree, but I’m not about to argue the point. Paradoxically, though, if someone wants to say that English girls invented punk rock, I’m ready to sign on.

All due respect to Gordon, and Patti Smith for that matter, but punk always felt like UK product to me. America invented rock’n’roll, but punk was theirs. And while Joe Strummer and Johnny Rotten were my heroes, Poly Styrene and Ari Up were my teachers. They were the ones toying with expectations and undermining gender roles. And with their bands (X-Ray Spex and the Slits, respectively), they were brutally honest about it.

Agreeing to disagree about punk’s birthright is probably the best way to proceed here, at least when the subject at hand (tangentially, anyway) is Lincoln Center honoring the two bands with a pair of concerts in its American Songbook concert series last month. The rationale was something about their impact on American music and I’m not about to argue that point, either. I was just glad for the excuse to ruminate and celebrate. The concerts—laudably free and held at the David Rubenstein Atrium with a rotation of local singers—were loose and spirited, full of love and posturing and female energy. There was also an evening dedicated to the California band Fanny and a “Mixtape: Women in Punk” night, neither of which I was able to make, but ruminate I did.

That three-word headline at the top isn’t about natty dread and punky reggae parties, it’s about existential dread. Existential crises aren’t punk. That’s what post-punk is for. Punk’s about revolt. Punk’s about offending people, upsetting things. It’s not about problem-solving, it’s straight-up accusatory. Reams have been written about punk and revolution, punk and reggae, punk and gender, punk and fashion, punk as an art movement. But what punk mostly is, and what everyone knows punk mostly is, is attitude. As a kid in the Midwest, I absorbed that attitude. More than the anarchy and rebellion and haircuts, I absorbed the attitude. In the (many) years since, I’ve come to realize that my personal punk ethos is a minority opinion, largely cribbed from Styrene and her band’s 1978 album Germfree Adolescents.

The 12 tracks are all about plastic and artifice, genetics and shopping centers. She’s a poseur, she declares, and her mind is like a plastic bag. She can’t read, write, love, hate; she knows she’s artificial, reared in a consumer society. The album is largely about the powers that really rule society, giant corporate cyclopes dictating our dreams and stamping out any sense of self. Ultimately, Styrene preaches “Identity is the crisis, can’t you see?”

The Slits 1978 album Cut, on the other hand, exploded with autonomy, even when it meant loneliness, even when it meant stealing cheese to have something to eat, while all around was addiction: to heroin, to fashion, to television, to toiletries. Typical girls, they sang, fall under spells while looking for—something. The Slits (Up, Viv Albertine and Tessa Pollitt) were anything but typical. These were, for me, the lessons of punk. It’s not about gender. Well, it is, I’m not about to argue that point, but it’s about individuality.

Nihilism is the easy way out. Poly Styrene and Ari Up were passionate and in the thick of it. They’re both gone now—Up in 2010 at 48 and Styrene at age 53 the following year, both of breast cancer. But punk lives on.

Punk’s undead. Anyway, I wanted to get all that off my chest. But I think what I’m supposed to be doing here is writing about records, and fortunately punk isn’t dead, although it seems like a zombie a lot of the time. There are still pilgrims around, true believers, trail blazers releasing hard-hitting records. The Dutch band the Ex, founded in 1979, and comparative toddlers Mclusky, founded in Wales in 1996, both have powerful new albums out: If Your Mirror Breaks (CD, LP and download on the Ex’s own Ex Records) released last month and Mclusky’s the world is still here and so are we (CD, LP, digital from Ipecac Recordings) out May 9.

Close to 20 people have passed through the Ex’s ranks during the remarkable 46-year run, with guitarist Terrie Hessels (who hit 70 last year) being the only one there since the inception. But the current three-guitar-and-drums lineup (no bass) has been at it for 16 years, when singer/guitarist Arnold de Boer stepped up for founding frontman GW Sok. That alone is longer than the life expectancy of the average punk band, and they’ve got their sound down, a consistent march, chug and jig and smart anarcho-sensibility rings through. “Spider and Fly” and “Great” are the choice cuts. Mclusky, meanwhile, only released three albums before a long (2005-2019) hiatus. The new album is their first since reforming and is a vitriolic blast. Singer Andy “Falco” Falkous is the only holdout from the first incarnation and is endlessly inventive in his variations of snide sing-song taunts delivered with the precision of a top-shelf rapper. They lean a bit closer to hardcore at times than the other bands mentioned here, but can also pull back to slow (well, midtempo), haunting, circles. “People Person” is the charming and vicious lead single, but “Not All Steeplejacks” is the sleeper hit.

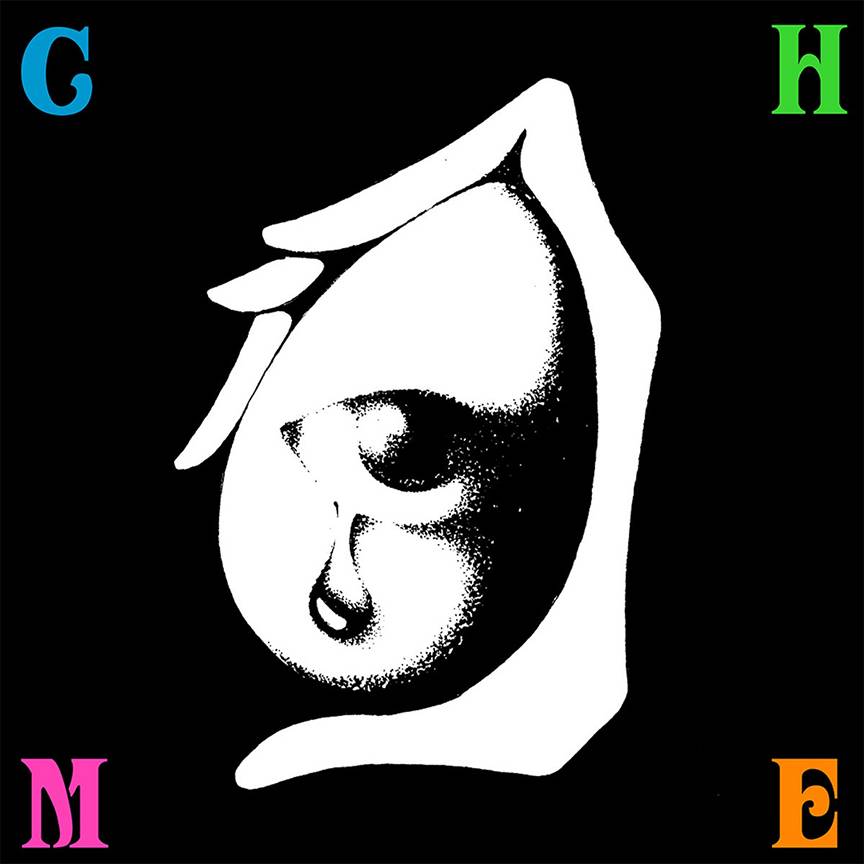

New riders of the punkish rage. Producer and soundtrack composer Jack Nietzsche once said that punks will never die, they will just keep living the same life over and over again. Or maybe that was Friedrich Nietzsche and he said it about everybody. Either way, punk lives on (and on and on), usually by virtue of another generation mimicking the same old rebellion while playing dress up. But occasionally there are passengers with new ideas aboard the nostalgia train. Chime Oblivion isn’t a bunch of kids, but it’s a new venture launched by John Dwyer (Osees) and drummer David Barbarossa (Adam and the Ants, Bow Wow Wow), joined by Osees percussionist Tom Dolas with Weasel Walter (Flying Luttenbachers, Lydia Lunch) on guitar and H.L. Nelly (Naked Lights, FKA Smiley) on vocals. Barbarossa and Nelly define the sound, his hyper-tribal drumming still so familiar and her yelps and shrieks bringing a bit of a Nina Hagen edge. ‘The Uninvited Guest” even calls back to OG punk referencing early rock’n’roll, making it retro-retro. The songs, co-written by Dwyer and Nelly, are poetic, insistent and a little bit mysterious. They’re also a little bit poppy and a lot of fun. Their self-titled debut came out last month (LP and download) on Deathgod.

Punk will live on at least as long as there’s a need for it. For the present, it’s in dire good health.

Author

Discover more from Red Hook Star-Revue

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.