Red Hook has already seen its fair share of transition. The fort that played a pivotal role in the Revolutionary War is long gone, as are the marshlands that surrounded the military structure. For about a hundred years the neighborhood thrived as a key port along the eastern seaboard, until the 1960s when break-bulk shipments gave way to containerization. Today, the port, while still operating, is a shadow of its former self after decades of disinvestment and insufficient maintenance.

After the port’s fall from grace, Red Hook became Brooklyn’s version of Staten Island: disenfranchised, neglected, forgotten. As mayor, Rudy Giuliani had plans in the late ’90s to turn Red Hook into a dumping ground — literally; in 1997, the administration announced that it was considering the peninsula as the site of a massive trash-processing facility. (These plans were, fortunately, thwarted by the Red Hook community.)

Instead, Red Hook became the home of artists, blue-collar workers and small businesses.

Soon, it’s poised to change again as the Brooklyn Marine Terminal redevelopment moves forward; whether the final result is a bustling maritime hub or a mixed-use community with luxury towers and LuluLemon, Whole Foods, Sweetgreen and Starbucks storefronts, it will drastically alter the fabric of the neighborhood.

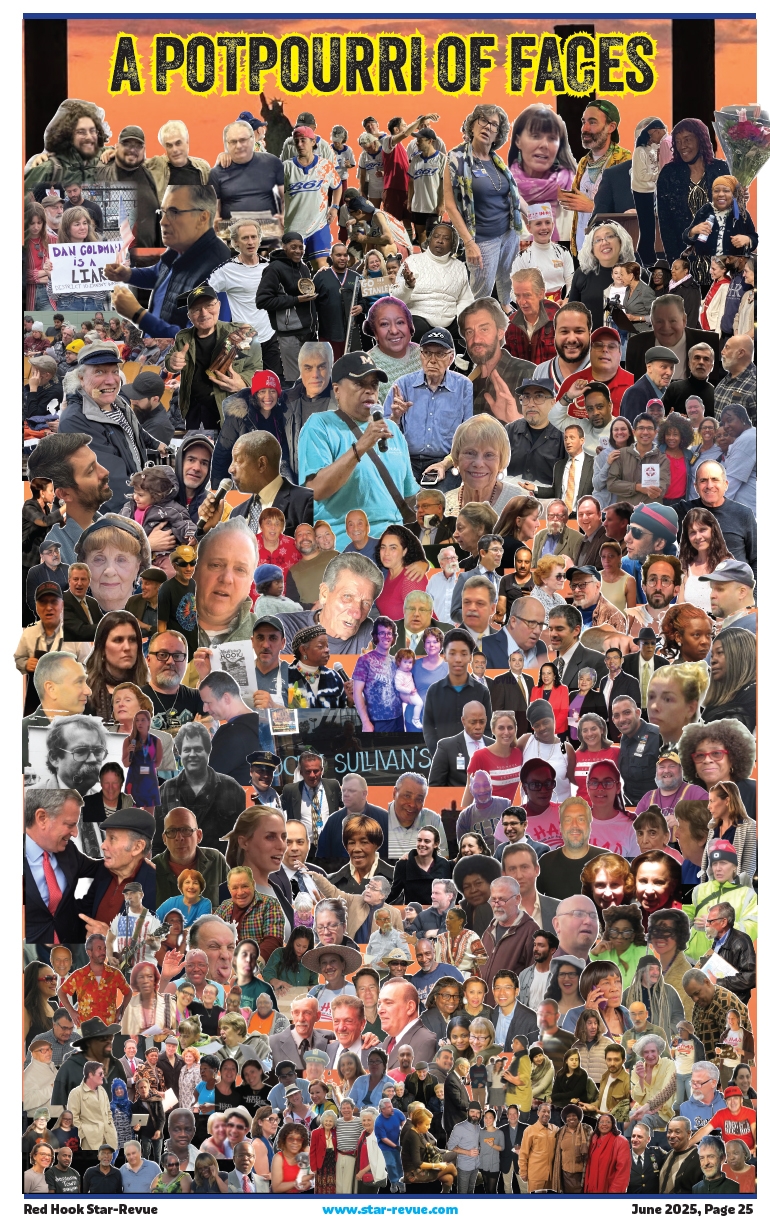

There are many who have made Red Hook into what it is today. But as the Red Hook Star-Revue celebrates 15 years of community news, we thought it appropriate to speak with two men who, in different ways, left marks that have lasted even after they left : John McGettrick and Greg O’Connell, Sr.

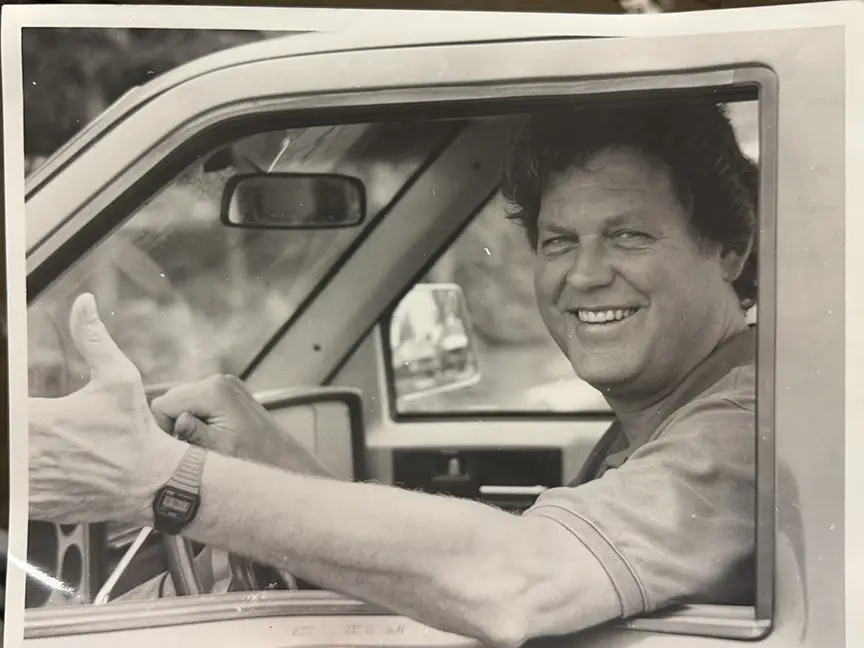

For decades, Greg O’Connell, Sr. — sporting a denim overall — used to drive around Red Hook in his silver pickup truck, checking in on his properties and developments.

And there are a lot of them. In 2019, it was reported that O’Connell — whose son, Greg Jr., since some years ago runs the family business — owned about $400 million of real estate in Red Hook, including Pier 41 and the Red Hook Stores, which he turned into a Fairway supermarket (now Food Bazaar)

O’Connell, who worked as a teacher by day and drug cop by night before he turned to real estate, began to acquire property in the neighborhood at a time when many lots along the water stood abandoned. In 1972, the City Planning Commission and Board of Estimate approved a 230-acre urban renewal plan to modernize the port and build additional housing. In anticipation of a massive expansion of the port — which would now focus on receiving containers — many residents left, rather than being forcibly displaced through eminent domain. But the city’s growing financial woes — which culminated in the Fiscal Crisis of 1975 — threw a wrench in the renewal plan. Work that had already begun was simply stopped. O’Connell recalls sewer lines along President Street left half-finished and buildings collapsing from changes to the water table.

“What I saw at the time were a lot of vacant lots and abandoned buildings,” he said. They did redevelop the container terminal into the size it is today, he noted, “but the rest of it was a disaster.”

As the city walked away, O’Connell, now 83, was on the board of the Community Board, chairing the Waterfront and Economic committee. “I looked at everything that was left over and I began to purchase vacant lands and buildings, either unoccupied or partially occupied, with the hope of having an impact on the community,” he said, adding that while buying one or two buildings can change a block, “If I could assemble large parcels of property, then I could put to work what the needs of the community were. It was a chance for me to rehabilitate and preserve historic buildings, readapt them for uses of today, to open up the waterfront for use by the public.”

Fairway, the upscale grocery chain, was one of O’Connells most well-known — and controversial — clients. He sees it as one of his biggest accomplishments.

What convinced him to rent to a supermarket in 2006 was walking through one of the neighborhood’s existing grocery stores with two of Fairway’s three owners. According to O’Connell, they explained to him how the food being sold, primarily to people living in the Red Hook Houses, wasn’t any good.

A boon and perhaps a bane

Fairway proved beneficial in many ways for the neighborhood, bringing in high-quality products and hiring hundreds of local residents to union jobs. But concurrently, some local residents complained that the store was too expensive for those in public housing, in particular after Superstorm Sandy. The store also brought in New Yorkers from across the city looking for specialty items and quality goods for cheap, spurring ongoing gentrification, and set a precedent for big-box stores and last-mile delivery facilities, some argue.

O’Connell calls himself a community developer, rather than ”just a developer,” citing his work on the community board and relationship with Ron Shiffman, the urban planner who co-founded the Pratt Center for Community Development (then known as the Pratt Institute Center for Community and Environmental Development). Shiffman’s work in Red Hook dates back to the early 1990s and is well-respected by many in the community.

O’Connell says the two often worked together. “I would always talk to him about my plans for the waterfront and those buildings — were we doing it right, were we inclusive — and trying to get as much support as we could on the needs of the existing community.”

Some critics have claimed that O’Connell, during his time in Red Hook, overpromised and underdelivered more than helped the community, particularly on developing housing.

But the Grand Poobah of the O’Connell organization counters that he has been involved in several affordable housing projects. He sold properties to the Fifth Avenue Committee — a community developer in South Brooklyn — to be used for affordable housing.

But the Grand Poobah of the O’Connell organization counters that he has been involved in several affordable housing projects. He sold properties to the Fifth Avenue Committee — a community developer in South Brooklyn — to be used for affordable housing.

“We sold it substantially below the market, with the promise that they would put in housing for people who had lived in the housing project, moved up economically and wanted to own property in Red Hook,” he said, referring to residents of Red Hook Houses.

He also supported the construction of IKEA, also a controversial project.

O’Connell contends his goal always was to serve the community first. “You have to have the community involved because they grew up here. Red Hook was a community where you attended the local church, the men worked on the waterfront or in related businesses to the waterfront, and it was a small, niche community. And no one knows what the needs are of that community better than the people who have lived there for generations,” he said. “You don’t have to squeeze out every damn dollar on a project.”

O’Connell wasn’t speaking about the Brooklyn Marine Terminal redevelopment, but his point lingers. The city’s Economic Development Corporation, which leads the project on behalf of the mayor, has for months drawn criticism for ignoring community input and selling out the waterfront to real estate developers.

“It’s too suffocating,” O’Connell says. “We know we need housing and that should be done, but you have sewer lines and gas lines and electric utilities — develop all of that! Get that inner part developed first before you start putting up huge buildings. It’s one thing to have a place to hang your hat; it’s another to have a place and a community that’s livable.”

Author

Discover more from Red Hook Star-Revue

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.