I stepped into the original Fedora, on West 4th and Charles, nearly 20 years ago. I was looking for a place to have a quick drink. Its neon sign drew me to its ivy-covered building, its entrance a few steps below street level.

Inside: red light, a pink portable stereo on the bar next to a glass bowl of pretzels. A phone booth. A drippy sink in the men’s room that smelled of basement, of damp. Small tables, covered with white cloths, most of them occupied by solitary diners—most of them older gay men.

To be a gay man of a certain age is to have experienced the devastation of the AIDS era. Fedora was near the old St. Vincent’s hospital, where so many suffered and died. What had these men seen? Whom did they lose?

I started going to Fedora weekly. The two waiters, George and Jonathan, shared bits and pieces of the restaurant’s history while circulating through the small room, chatting and joking, ducking behind the bar to mix drinks, carrying them to the tables on little trays. They’d sniff the cocktails before setting them down and sometimes bring them back to mix them again.

When the elderly Fedora made her appearance each night, everyone clapped. She’d started as a hostess and inherited the business. She owned the building and lived upstairs. She made the desserts herself; her specialty was icebox cake.

They still used the original 1950s’ menus, covering the old prices with white stickers and writing in the new ones. The dishes, like Eggs à la Russe—a hardboiled egg sliced and served on iceberg lettuce, covered with Russian dressing—stayed the same.

On busy nights George would make two singles sit together to make room for new arrivals. I remember him whispering, “Don’t order the steak,” right after Fedora had passed our table announcing it as the nightly special—a warning of untold disasters happening back in the kitchen. But you didn’t come to a place like Fedora for the food. You came for the community.

Entree

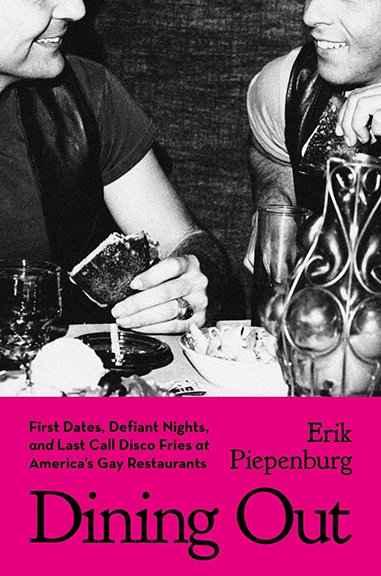

“Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants” serves up the atmosphere of restaurants like Fedora—singular, unpretentious and emotionally generous. Erik Piepenburg, a longtime New York Times contributor, traveled across the country to record stories about this important but largely undocumented piece of gay history: the places that feed the gay community in every sense of the word.

What makes a restaurant gay? Sometimes it’s because the owners, chefs or servers are gay. Sometimes it’s because the regulars make it that way—by showing up again and again until the place feels like theirs. It’s less about having a rainbow flag and more about the vibe.

The restaurants Piepenburg profiles include radical feminist vegetarian co-ops, diners, donut shops and drag brunch venues (“straighter than ever” and “as corporate as it gets”). These places are not just in gay meccas like San Francisco but in small towns across Wisconsin, Ohio and Florida. Close to home, Piepenburg singles out Julius’, the West Village bar where members of the Mattachine Society staged the 1966 “Sip-In,” demanding to be served as openly gay men, Chelsea mainstay Elmo and the East Village queer fine-dining restaurant HAGS. Much space is devoted to the legendary, long-shuttered Florent, a Meatpacking District pioneer whose success led to the gentrification of the neighborhood and the restaurant’s demise.

What connects these far-flung places is not cuisine or clientele but the function they serve. These are places where trans people try on new names and selves, where gay seniors feel seen and supported, where people meet to flirt, vent, mobilize or simply be around others like themselves.

What emerges through these stories is a rough history of gay public life: how, in the 1920s and ’30s, they mostly flew under the radar; how, after World War II, they became more visible, especially in cities; how the 1970s put neighborhoods like the Castro and the West Village on the map; how the 1980s’AIDS crisis brought unimaginable loss; how the 1990s mainstreamed gay identity; and how the 2000s and the rise of the internet shifted so much of gay social life online.

Piepenburg writes with reverence for gay elders who paved the way for the life he lives now and shows curiosity about a younger generation that seems to be making and breaking its own rules.

He also shares stories about his own bad dates and lonely nights, about meeting his partner and the quiet joy of eating rice pudding alone with a book. He’s a big fan of diners—affordable, accommodating, open late—and advises ordering something “that must be made fresh to order, not food that’s sitting around waiting to be reheated.”

The power of this book lies less in the places than in the people: a chorus of voices remembering what it means to feel at home in a public place. What Piepenburg’s personal and poignant work ultimately documents is connection—what it means to show up hungry and find more than just a meal.

Dessert

The neon sign still hangs outside Fedora, but the inside has been completely gutted. It’s an entirely different restaurant now. I don’t know what community is served by its “low-intervention wines” and “seasonal cooking.” But it doesn’t sound like the cash-only kind of place it used to be.

I was there on closing night for the original. I brought a huge group of friends I’d taken there over the years who, like me, had fallen in love with the crazy charm of the place and the hijinks it served.

George came over to the table to take our order and shook his head. “You can’t all start with the Eggs à la Russe,” he explained. “We only have one egg left.”

And he went to the kitchen to get it, to show us.

Author

Discover more from Red Hook Star-Revue

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.